Youth and Beauty: Art of the American Twenties is a new exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum, which examines young people’s powerful influence on the visual culture of the 1920s. Our film will look closely at Flappers, and how this American youth culture, their jazz, fashion, and partying, would inspire teenagers around the world. So we were intrigued to see this show, and excited to discuss our overlapping interests with the exhibition’s curator Terry Carbone.

Matt Wolf: When many people think of the 1920s, cliché costume party flappers doing the Charleston come to mind. In our archival research for Teenage we’re trying to show a more nuanced everyday life from that era. Was that one of your goals with the exhibition… to help viewers re-imagine this period?

Terry Carbone: When I started work on a 1920s exhibition, I actually expected to find imagery of the popular culture we know through sociological studies (both contemporaneous and more recent) or novels of the era. So I was quite astonished to discover the degree to which artists, while intent on demonstrating their modernity and their engagement with the physically present modern world, also hoped to distance and distinguish themselves from a popular culture that they perceived to be too frivolous, materialistic, consumerist, and essentially shallow. Flapper culture really did exist among the young in 1920s America, even among the less affluent. In an amazing book about the decade’s youth culture, Paula Fass discusses the many changes to the lives of teenagers in the 20s, when children were more coddled by their parents, and had less expected of them. Kids themselves, adjusting to car culture and movie idol role models, disregarded traditional social codes like eating meals at home on a regular schedule, and dressing like their parents. Again and again in fiction of the era one reads narratives about generational conflict, as rules and practices go by the wayside, and the newest leisure pursuits and unregulated schedules took over their lives. What was startling to me was the degree to which artists (and many culture critics), in their art and in their memoirs and letters, disdained the new youth culture. While they embraced the new mores of liberated sexuality and sensuality, they were more insistent on framing the change as physical/creative authenticity–a sustaining contact with the real/natural–that would be something of an antidote to machine age routination and would lend gravitas liberated behaviors. Most of these artists were well into their adult years–and had some distance from the dominant teenage culture.

MW: Sexuality and androgyny are big themes in the show. For instance, Margrethe Mather’s Billy Justema, or some of the more scantly clad beach swimmers. Do you think artists played a significant role in opening up new types of gender and sexual expression? Or were they just documenting the changing culture around them?

TC: Sexuality and sensuality were absolutely central to artistic expression in twenties America, as were the notions of individuality, authenticity, and austerity–all words used often by artists and critics throughout the decade. I think more open modes of gender and sexual expression were emerging in the popular culture, and artists were trying to achieve an alternative expression equally grounded in these shifted social codes. I think that the widely popular currency of Freudian theories (however inexactly interpreted) in the twenties less to a general dismissal of repression of any sort, but that visual artists sought to elevate sexually expressive body imagery both by the idealization of bodies (in painting and sculpture) and the sober “purity” of photographic close-ups. Visual artists very deliberately avoided explicit sexual expression, which they regarded as un-nuanced or coarse; Weston, for one, believed D.H. Lawrence (for example) was far too explicit–that his novels were more like sex manuals–and saw his own (Weston’s) very sensual, and indeed daring nudes as more elevated and earnestly authentic.

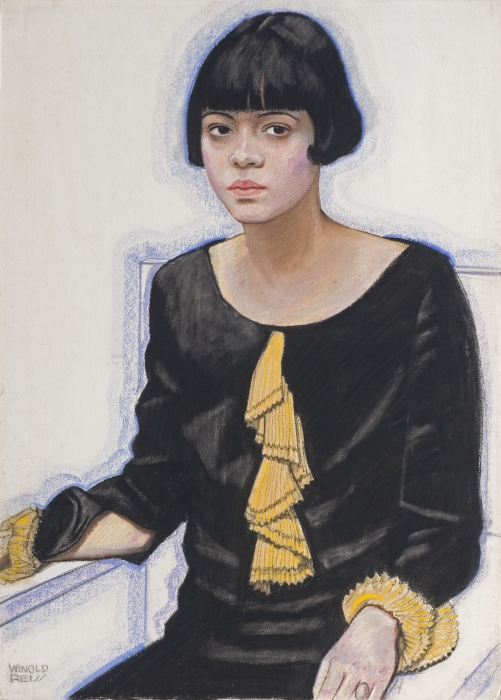

Winold Reiss (American, 1886-1953). Sari Price Patton, 1925. Pastel on Whatman board, 30 x 21 1/2 in. (76.2 x 54.6 cm). Private Collection. © The Reiss Partnership

MW: It’s really interesting how popular culture filtered down—whether it was young boys aping Rudolph Valentino’s style, or in an artwork like Winold Reiss’s Sari Price Patton, young women copying the style of Flapper “It” girl Clara Bow. Was this one of the first eras where art consciously reflected the styles and fads of popular culture?

TC: Having been in graduate school in the theoretical ’80s, I was taught not to use the word “reflected,” as artists do not “reflect” actualities but rather create works inevitably ‘informed” by them—the context was inescapable. That said, movies were a ubiquitous influences on all strata of American society—by 1929, 90 million movie tickets were sold every week in the US!—as were fashion and beauty magazines—and kids even in the smallest towns were focused on the same fashion-making stars. One of the most interesting things about twenties movies was, however, their insistent moralizing vein. No matter how playful or naughty girls were at the outset of these movies, if they didn’t ultimately conform to traditional heteronormative social roles (marriage, that is) they met with unpleasant ends. But in terms of style and fashion–all of the new liberating modes–bobbed hair; corsetless freedom; thin, sheer fabrics; short hems; silk stockings–that allowed girls to accept and expose their sexuality, were purveyed in ubiquitous and highly influential imagery.

George Copeland Ault (American, 1891-1948). Brooklyn Ice House, 1926. Oil on canvas, 24 x 30 in. (61 x 76.2 cm). Newark Museum, Purchase 1928 The General Fund, 28.1760

MW: There is lots of imagery of a ‘new world’ in the show, particularly the machine culture of the era. Do you think the 1920s was the first period when people really idealized youth (and their beauty) as symbols of the future?

TC: There is indeed quite a bit of imagery that presents newly dense and vertical urban settings, and industrial technology. Artists represented these subjects gingerly, and throughout attempted to assert their individualized view of these new actualities, so as to distinguish themselves from the supposedly unintuitive engineers who had designed the new, functional forms of in the environment.

I don’t think the 1920s was the first period in which people idealized youth as symbols of the future—I’m not even sure that they were symbolic of the future in the 1920s—I think the ethos of 20s youth was in fact entirely present-oriented. I think you see children-as-America’s-future more clearly in the mid-nineteenth-century. It’s important to remember that the twenties was very much a post-war period, even though the reactions to the war are sometime written into the visual culture with great subtlety. I would emphasize that youth culture in the twenties was very present-minded—and in a way that the older generation found disconcerting and even troubling.

MW: Something I’ve thought about the 1920s is that ‘Youth’ is more of an idea than an age. For instance, Flaming Youth or Bright Young Things were often in their mid twenties or post-collegiate. Do you think this desire to identify as ‘young’ regardless of age was about freezing time, or trying to stay young forever?

TC: I think that in the 1920s people in their twenties were indeed still “youth.” Except for “petting” and sex, more traditional adult behaviors were being postponed a bit. But there was a real limit to how long one could perpetuate “youthful” behavior. Drinking may have been an exception. But the generation that had come of age just before the war had a very different view of things.

James Ormsbee Chapin (American, 1887-1975). George Marvin and His Daughter Edith, 1926. Oil on canvas, 38 1/4 x 44 in. (97.2 x 111.8 cm). Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Joseph E. Temple Fund. © James Cox Gallery at Woodstock for the James Chapin Estate.

Youth and Beauty: Art of the American Twenties at the Brooklyn Museum is open until January 29.